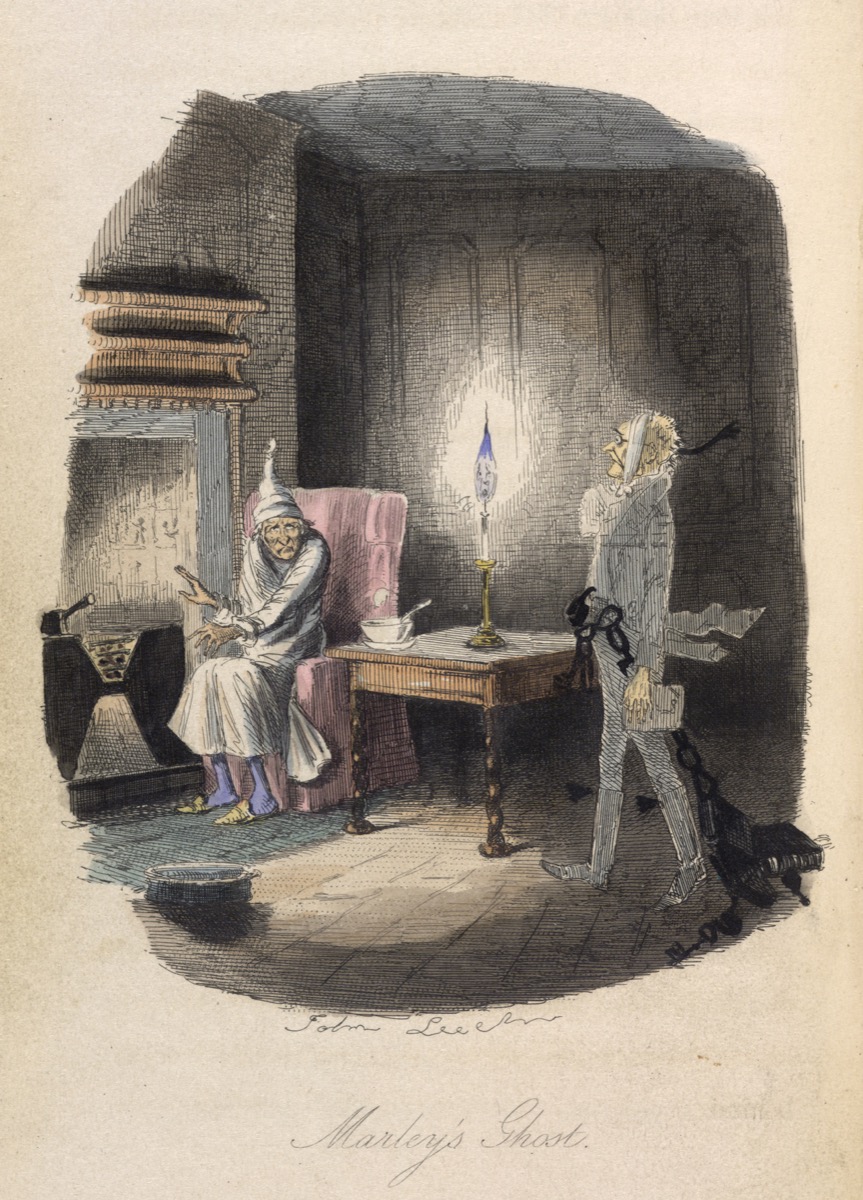

So, we consulted Brian Earl, host of the Christmas Past podcast, blog, and YouTube channel, to find out more about the strangest Christmas traditions of yonder yuletides, from telling supernatural stories to hiding coins in cake. Keep reading for some long-gone practices that you may want to revive for you festivities, and for more holiday trivia, check out 55 Fun Christmas Facts to Get You in the Holiday Spirit. You’ve no doubt read Clement Clarke Moore’s iconic 1823 poem “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas,” which includes the line, “The children were nestled all snug in their beds / While visions of sugar plums dance in their heads.” But have you ever stopped to think about what a sugar plum actually is? “Originally, these were caraway seeds or cardamom pods—some kind of spice that was then coated in sugar,” Earl explains. (Modern holiday recipes involving dried fruits or nuts are actually “not at all authentic, but just something that Alton Brown made up,” he says.) In this case, the word plum comes from its non-fruit-related usage, meaning “desirable,” such as in the term “plum job.” For some fascinating facts about the centerpiece of your decor, check out 30 Amazing Christmas Trees Facts to Make the Holidays Extra Magical. Fruitcake has gotten a bad rap as of late. But placing fruitcake under your pillow actually has some pretty sweet origins. “If you ate a piece of fruitcake—especially if it was from a wedding—and put [the remainder] under your pillow at night, legend said you’d dream of the person you will marry,” says Earl. And this isn’t the only antiquated Christmas tradition involving love. Christmas revelers in the 17th century would also do things like throw food at the wall to see if what stuck spelled the name of a lover. They’d also toss shoes into a tree—and if they hung there, the thrower would be married within the year. Today, English royalty continues to serve fruitcake at Christmastime gatherings as a nod to the tradition, says Earl. In 12th-century France, a donkey would be led in a procession through the center of town to the local church, where a service was in session. The donkey would remain next to the church’s altar for the duration of the service, and congregants would mimic its bray in a call-and-response with the priest. This tradition, known as the Feast of the Donkey, was accompanied by “raucous parties that usually got out of hand,” says Earl. The celebration became such a problem that many towns eventually banned it. For more holiday trivia sent right to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter. Derived from the influence of Roman Saturnalia celebrations, social inversion was a popular Christmastime practice centuries ago, says Earl. This would typically involve the election of a “boy bishop,” or child, to run the church in lieu of a minister during the Feast of Saint Nicholas on Dec. 6. In the most extreme examples, you’d wind up “with some three-year-old running around leading the whole thing,” Earl explains. Today, the Christmas season runs from Thanksgiving to Christmas Day. But that wasn’t always the case. “Before, it was the other way around,” explains Earl. The months leading up to Christmas were considered Advent, which, similar to Lent, was considered a time of restraint for Christians. Instead, Christmas season was from Christmas until the Eve of the Epiphany (Jan. 6). And the biggest celebrations were actually held on that final day, known as “Twelfth Night,” which served as the inspiration for William Shakespeare’s play of the same name. For the festive flick you need to watch this year, check out The Best Christmas Movie of All Time, According to Critics. Many games and Christmas celebrations were once held on Twelfth Night. And one of those traditions, according to Earl, was to “bake a cake and hide something in it, like a string bean or a coin,” which is similar to the modern tradition of finding a bean or figurine in a king cake served on Mardi Gras in the South. Whoever found the item in their slice of cake on Twelfth Night would “lead the evening’s festivities,” Earl explains. Under the tradition of the Lord of Misrule, which was popular in medieval courts, a “jester or clown would become mayor of the city for the Christmas season, suggesting all sorts of funny things that everyone would have to do,” says Earl. Depending upon the village’s ruling structure, this was also sometimes known as “The Abbot of Unreason.” This tradition was meant to provide entertainment throughout the entire Christmas season. Eventually, the raucous celebration was banned in 1541 by Henry VIII and banned again by Elizabeth I after a brief resurrection by her predecessor. For some fascinating regional celebrations that still exist, check out 20 Ways Christmas Is Celebrated Differently Across the U.S. Wearing costumes used to be a traditional part of the Christmas celebration, says Earl. In one famous instance, a group of 13th-century nobles burned to death when the tar on their “forest savages” costumes caught on fire. King Charles, meanwhile, narrowly escaped the incident, and the practice was henceforth banned within his court. “Caroling used to look a lot more like trick-or-treating,” says Earl. In fact, in 19th-century Europe, it was an occasion for poor folks to request gifts from wealthy landowners. According to Earl, “they’d go from house to house and say, ‘OK, we’re going to sing you a song and you can either invite us in for food or a drink… but if you don’t, you never know what’s going to happen to your yard.’” Yikes! “In the song ‘It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year,’ you hear the line ’there’ll be scary ghost stories and tales of the glories,’ and may wonder why there would be scary ghost stories on Christmas,” says Earl. In addition, you might be curious as to why “A Christmas Carol,” one of the most famous Christmas stories of all time, is a ghost story. Well, the Victorians—who helped cement many of our modern American ideas of Christmas—loved scary stories. In fact, “A Christmas Carol” was far from the only Christmas-themed ghost story Charles Dickens wrote, says Earl. Yes, Christmas was once more spooky and scary rather than warm and fuzzy. And it wasn’t just ghost stories that once made Christmas the most eerie time of year. “There used to be a huge supernatural component to Christmas,” says Earl. For example, “in some parts of Europe it was believed that supernatural activity was at a high on Christmas Eve, sort of the way it is on the Day of the Dead.” Additionally, in Germany and Poland, if a child was born on Christmas Eve, they were considered more likely to be a werewolf. In 1938, Coca-Cola and artist Haddon Sundblom decided to depict Santa as a “six-foot, full-grown human grandfather,” says Earl. Due to their massive marketing budget, Coke’s version of Santa Claus spread far and wide, and soon became the standard image of Santa throughout the United States and much of Europe. Before that, however, descriptions of Santa were “all over the map,” Earl explains. This included variations of Santa as an elf and a gnome—in fact, much of the time, he wasn’t depicted as fully human at all.ae0fcc31ae342fd3a1346ebb1f342fcb Prior to the modern adoption of reindeer and elves in Saint Nick’s mythology, Santa’s helpers were a little more sinister. Instead, he would have “these gruff characters that walk around with him and dole out punishment,” says Earl. This includes the menacing Krampus, a horned goat-demon who punishes naughty children, and whose presence on Christmas is still recognized in Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, and Slovakia. This superstitious Christmas tradition has fallen out of favor in recent years, but “first footing” was the belief that “the first person to cross the threshold [of a home] on Christmas Eve is considered good luck, especially if it was a dark-haired gentleman,” says Earl. It was typically observed in England and Scotland. “The Christmas tree was a regional German tradition,” says Earl. And for many centuries, you would have been hard-pressed to find people celebrating around a tree outside of Germany. Decorating Christmas trees only became popular internationally after Prince Albert and Queen Victoria were sketched standing next to one at Windsor Palace in a 1848 image published in the Illustrated London News, titled “Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle.” Soon, the Brits, Americans, and other Europeans began doing the same.